Key Takeaways

- China’s export restrictions on seven key rare earths are disrupting supply chains and driving up prices, especially in renewable energy, defence and tech sectors.

- Australia is positioned to benefit from China’s restrictions by expanding its mining and processing capabilities. This will allow it to supply critical rare earths to allied countries.

- To seize the opportunity, miners and government must fast-track rare earth infrastructure and build strategic partnerships—despite environmental and cost hurdles.

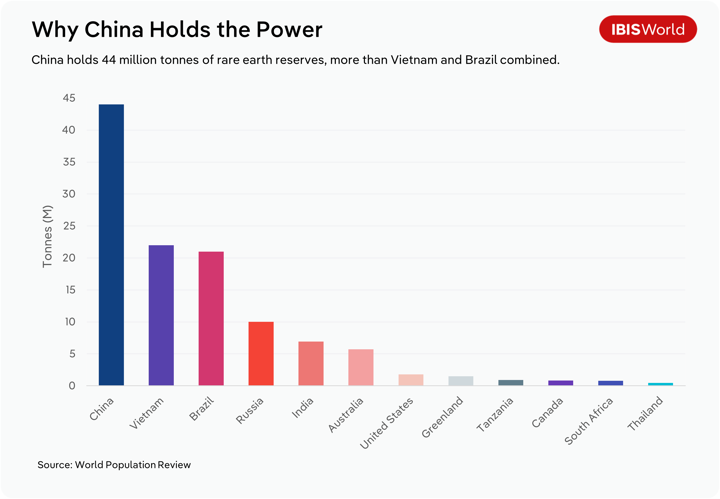

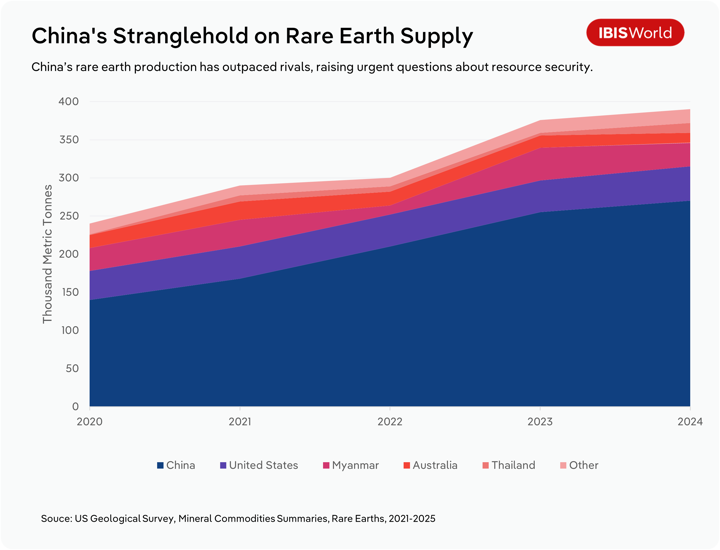

On April 4 2025, China tightened its grip on the global rare earths supply, restricting exports of seven critical elements as geopolitical tensions rise. These minerals, essential to electric vehicles, advanced defence systems and renewable infrastructure, are cornerstones of the modern economy. With China controlling both the world’s largest reserves and the lion’s share of processing capacity, the move is sending shockwaves through global supply chains.

While major economies like the US and EU scramble to secure alternative sources, the restrictions also open a door for Australia. With rich deposits and growing government support, Australia could step into a strategic role, if it can overcome major infrastructure and policy hurdles.

What are rare earths and why do they matter?

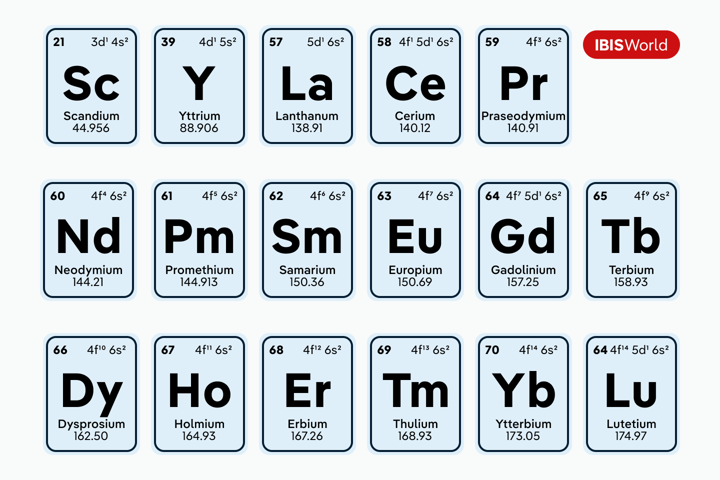

Rare earths are a group of 17 chemical elements, with deposits found in over 34 countries, known for their magnetic, optical and chemical properties, which make them essential to modern manufacturing. Despite the name, they’re not especially rare, but they’re difficult and expensive to extract in usable form.

These elements underpin a wide range of advanced technologies. They’re used in high-performance magnets for electric vehicles, wind turbines and other renewable energy infrastructure, key components in semiconductors and smart phones, and specialised alloys in aerospace and defence. For example, a single F-35 fighter jet contains nearly 900 pounds of rare earths, while Virginia-class submarines use over 9,000 pounds.

What China’s ban means for the global market

China dominates the supply of rare earths, accounting for around 70% of the volume of mined rare earth production. China’s export restrictions focus on seven rare earths in particular: dysprosium, gadolinium, lutetium, samarium, scandium, terbium and yttrium. With the exception of samarium, these are all heavy rare earths, which are in shorter supply and dominated to an even greater extent by China.

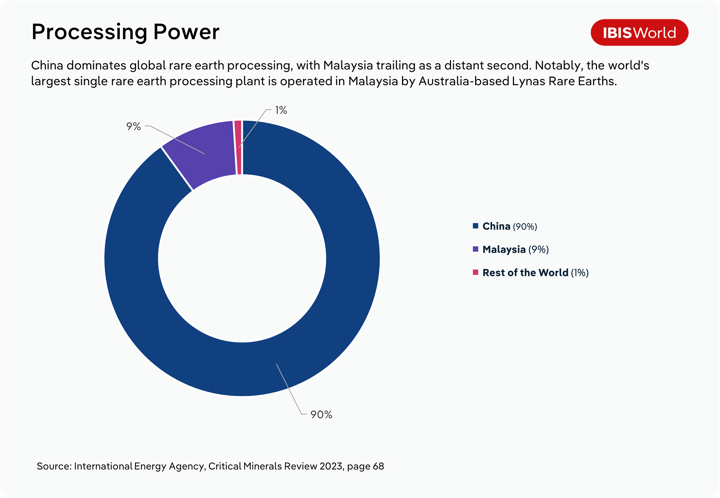

Not only is China the major rare earth miner, it also contains 85% to 90% of processing and refining capacity. China’s dominance in processing rare earths is as strategically important as its mining control, and a key reason the restrictions are so disruptive. The country controls almost all heavy rare earth processing, following the closure of the only other processing facility in Vietnam in 2024 due to a tax dispute.

China has been building up its dominance across the rare earth supply chain for decades. The export restrictions require all companies to attain special export licences. As companies around the world wait to gain approval from China, delays in manufacturing are already being felt, placing substantial pressure on global supply chains and upward pressure on rare earth prices.

Ramifications for the United States were set to be wider-reaching. 28 US-based companies (almost entirely in the aerospace and defence industries) were added to an export control list, preventing them from accessing the seven rare earths. However, following recent trade negotiations between the US and China, these companies have been taken off the export control list, and now face the same licensing hurdles as other companies around the world.

Australia’s moment

Australia is well positioned to benefit amid global supply disruptions and a growing demand for rare earths. With rich deposits, growing government support and constrained supply from China, the country has a strategic opportunity to become a more prominent supplier – if it can overcome key bottlenecks.

While Australia is gradually building up its rare earth mining capacity, in order to be a significant alternative to China, it needs downstream processing capacity. There is currently minimal processing in Australia, largely due to concerns over the environmental impacts of such activity. In fact, a project by France-based Rhone-Poulenc to build a gallium refinery in Pinjarra, Western Australia in the 1980s never eventuated in large part due to environmental regulatory delays. However, several Australian companies are taking steps to address this gap by investing in domestic processing and refining infrastructure.

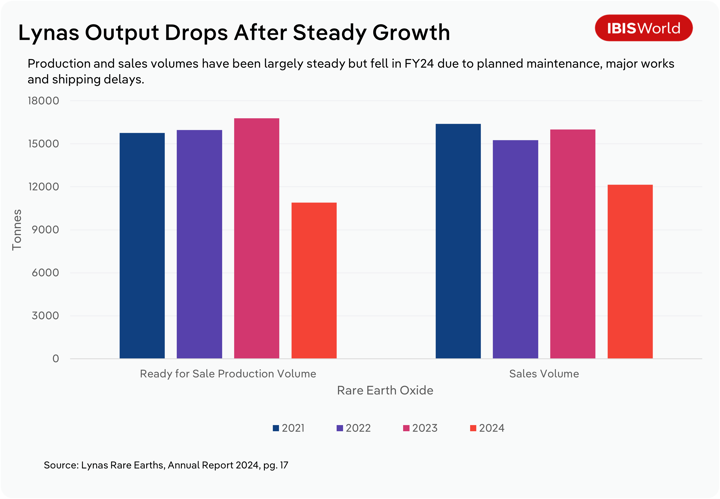

In 2024, Australia was the fourth largest rare earth mining nation, producing approximately 13,000 tonnes of rare earths - equivalent to 3.33% of world production. The largest rare earths miner in Australia, and the largest outside of China, is Lynas Rare Earths (Lynas). It operates the Mt Weld site in Western Australia, currently producing light rare earth elements neodymium and praseodymium. These are key for the production of magnets used in a range of products including electric vehicles, wind turbines as well as communications and weapons systems. Deposits of the heavy rare earth dysprosium have now also been found at the site. Major processing of the rare earths is complete at its plant in Malaysia, which is the largest single rare earth processing plant in the world.

In addition to Lynas, there are other rare earth miners establishing mine sites in Australia, though they have not yet reached production. These include Iluka Resources, Australian Strategic Materials, Northern Minerals, Arafura Rare Earths and Wyloo Resources.

BHP and Rio Tinto - Australia’s two major resource companies - have eschewed rare earth mining and other critical mineral mining in Australia, due largely to volatile prices and lack processing capability. BHP has completely avoided the sector, while Rio Tinto has focused on overseas opportunities for scandium, gallium and lithium. As a result, this potential major source of investment in rare earth mining is, at this stage, not forthcoming.

With China restricting exports and the US lacking domestic refining capacity, Australia has a strategic opening to supply rare earths – but it needs viable export pathways. Several options could help bridge the gap:

- Export processed rare earths directly from Australia: If local refining capacity can be scaled up, this would allow direct supply to the US and its allies.

- Partner with third countries for processing: Australian mining companies could export unrefined materials to countries like Malaysia or South Korea, where processing infrastructure already exists or is being developed.

- Invest in US-based processing facilities: Either independently or through joint ventures, Australian firms could build or co-own refining plants on US soil, creating a secure supply chain closer to end-users.

These strategies would not only diversify supply away from China but also position Australia as a trusted source of critical minerals for global partners.

Who’s exposed and who stands to gain?

Mining sector

Australia’s Mining sector is set to be the major beneficiary from the export restrictions put in place by China. The global transition toward electric vehicles, renewable energy and advanced electronics is driving a surge in demand for rare earths, positioning Australia as a strategically important supplier, amid constrained supply from China. This sector-wide development has broad implications for mineral extraction, export markets, and Australia’s role in global supply chains.

The expansion of rare earths extraction from both carbonatite rock and mineral sands increases the diversity and value-added potential of Australia’s mining portfolio. Major players such as Lynas Rare Earths, which operates in the Manganese and Other Mineral Mining industry, and Iluka Resources, which operates in the Mineral Sand Mining industry, are leaders in these respective rare earth mining opportunities.

Rare earths are also being discovered in clay deposits. This offers a potential expansion opportunity for the $4.4 billion Rock, Limestone and Clay Mining industry. Currently, clay only accounts for 4.2% of industry revenue. In February 2025, Critica Limited discovered the largest clay-hosted rare earth deposit in Australia. Contained in the discovery is the China-restricted rare earths, dysprosium, terbium, samarium, gadolinium, lutetium and yttrium as well as neodymium and praseodymium. However, it is more difficult to extract rare earths from clay-hosted rare earth deposits, compared to ionic clay deposits. Developing a cost-effective processing method will be key to clay-hosted rare earth production like those found by Critica.

Processing, infrastructure and pricing power

In order to take full advantage of the abundant rare earth deposits, Australia will need to develop processing and refining infrastructure. Companies like Lynas and Iluka are moving into processing, boosting the Gold and Other Non-Ferrous Metal Processing industry. Lynas is already investing in expanding its recently opened Kalgoorlie Mixed Rare Earth Carbonate processing facility, with processing capacity set to rise from 10,500 to 12,000 tonnes by 2025-26. Iluka Resources plans Australia’s first integrated rare earths refinery at Eneabba, Western Australia, to process rare earths from mineral sands and, later, heavy rare earths from Northern Minerals’ Browns Range site. The refinery is not set to come online until 2027. Arafura Rare Earths is also building a processing plant at its Nolans Project in the Northern Territory to export separated rare earth oxides.

Rare earths are often remote, so logistics industries like the Rail Freight Transport and Water Freight Transport industries would likely benefit from increased demand and infrastructure upgrades.

The construction of these processing and refining facilities has been supported by a number of government loan programs, and such assistance will likely remain necessary for the development of any new facilities. For example, Iluka Resources received a $1.25 million loan from Export Finance Australia in 2022 and received a further $400 million dollar loan in late 2024. The National Reconstruction Fund Corporation established by the Federal Government in 2023 invested $200 million in Arafura’s Nolan Project. Onshoring processing and refining is crucial in positioning Australia as a more self-sufficient and influential player in the global rare earth supply chain, reducing reliance on China and supporting growth of downstream manufacturing industries.

The increasing ability to mine and process rare earths domestically may help Australian producers negotiate better pricing. Lynas has historically sold its processed rare earths to Japan and matched the price that China charges Japan. So, if China’s restrictions push up the prices paid to Japan, then this will push up the price Lynas charges, boosting company revenue. Furthermore, Iluka believes that China historically has manipulated prices. The company has said they would be able to negotiate their own prices for the rare earths that they process. This claim has been doubted, but if China is going to restrict supply to defence firms and other buyers, then maybe Iluka would be able to set their own prices – due to the lack of other choices.

Who’s at risk?

While the Federal Government is attempting to bolster advanced manufacturing capabilities in Australia through the Future Made in Australia Act, the country’s currently limited high-tech manufacturing base means it is less directly exposed to rare earth shortages than countries like the US or Japan. For example, over 90% of domestic demand in the Communications Equipment Manufacturing industry is met through imports. However, some specialised sectors will still face disruption.

Defence industry manufacturers like BAE Systems Australia and CEA Technologies rely on imported rare earth metals for radar systems and other critical components, and they will be impacted by delays stemming from China’s new export restrictions.

The Metal Coating and Finishing and Electric Cable and Wire Manufacturing industries are also likely to face some disruption. Rare earths are used in specialised alloys and surface coatings for improved hardness, as well as improving durability and conductivity of cables and wires. If Australian rare earth miners are successful at establishing processing plants, then this could significantly boost the local value chain over the long-term, supporting manufacturers in these industries.

How Australian businesses can respond

Rare earth processing involves very long lead times, so mining companies focus on getting extraction underway as soon as possible. Early action allows time to identify offshore processing partners or begin building local capacity. In this sector, it is not a matter of being quick, but of being early. It’s not about exporting next year, but about starting to dig the hole next week, so to speak.

For processors and investors, the key opportunity lies in accelerating the development of domestic refining infrastructure. Support from government loan programs will remain important for scaling viable facilities. Co-investment in overseas processing, such as in the US or South Korea, may also offer a faster route to market while local infrastructure is built.

Manufacturers, especially those in defence, metal coatings and cable production, should closely monitor developments in processing capacity and pricing. While Australia has limited exposure to rare earth inputs overall, specific industries may face delays and increased costs.

Risk exposure is concentrated on China and its geopolitical allies like members of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation and BRICS Plus. For Australian businesses involved in the rare earths supply chain, this creates vulnerabilities from multiple directions. If trade or broader geopolitical tensions escalate, China could pressure these nations to limit or ban trade with Australia. Conversely, the US may pressure allies like Australia to reduce trade with these countries. In either scenario, Australian businesses would face significant disruptions to their rare earth supply.

Across the supply chain, having access to up-to-date industry data on production, processing and pricing allows firms to make more informed decisions. Monitoring global trends enables businesses to anticipate market shifts, identify reliable partners, strengthen procurement strategies and respond to a changing geopolitical environment.

Final Word

China's recently announced rare earth export restrictions have profound implications for global supply chains. Rare earths are an essential component of machinery and equipment for the defence, clean energy and electronics and technology sectors. China is in a dominant position, controlling most of the world’s rare earth production and processing output, heightening vulnerabilities and creating urgency for finding alternative sources.

Australia, with its significant rare earth reserves and emerging processing efforts, stands to benefit from rising global demand and prices. Driving up output of mined rare earths and constructing onshore processing infrastructure will require accelerated investment supported by government initiatives. Timely action, cross-border partnerships, and proactive risk management will be essential for Australia to meet the moment and enhance its position as a strategic partner to its allies.